Grave of the fireflies - an emotional masterpiece

Being in the western or the eastern part of the world has never stopped fans from taking a moment to appreciate exceptional content and those who love the Japanese culture of anime most certainly will get their heads out at the mere mention of the name “Studio Ghibli”. Studio Ghibli has been, by far, the most influential animation studio that has brought about the revolution in anime industry in Japan. With all the movies that the studio has produced over the years, be it Totoro or Spirited Away, there is not a single feature film that hasn’t stood out uniquely with a background of its own. The brilliant mind of Hayao Miyazaki has led to powerful storylines such as Howl’s Moving Castle and Princess Mononoke which manage to extensively present the recurring theme that Miyazaki has always preached. Over a career spanning five decades, Miyazaki seems to have had a strong and almost unbreakable bond with three notions that are prominent throughout his movies i.e. wind, women and revolution. The theme of Ghibli strongly resonates with these ideas along with a lingering emphasis on pacifism. With the big deal that Miyazaki is, we’re here to talk about the second most important person in the Studio Ghibli franchise and a lifelong friend of Miyazaki, Isao Takahata and his beautiful creation that is “Hotaru no haka” or more commonly known as “Grave of the fireflies”.

Takahata has been a crucial peg in the Ghibli machine over the years and having produced masterpieces like Pom Poko, it’s hard to argue otherwise.

Centering on two kids who try to survive post world war II Japan, there’s not a lot of movies that can be boiled down as easily as this one compared to other works that Ghibli has blessed us with. For any viewer, two things are prominent- First, the animation is excellent and the story is well written and second, it’s not exactly a joyful, happy film that will leave you with a warm feeling in your heart. It’s just sad. Prohibitively, unremittingly sad. And it’s not exactly the ideology you have in mind when a Ghibli film can be expressed so simply. But the more you immerse yourself in the story, it stops being a movie and becomes more of an unending duty that you wish will go the other way in every moment. However satisfying it feels to understand a movie this way, it forecloses our ability to understand the movie further in all its depressing glory.

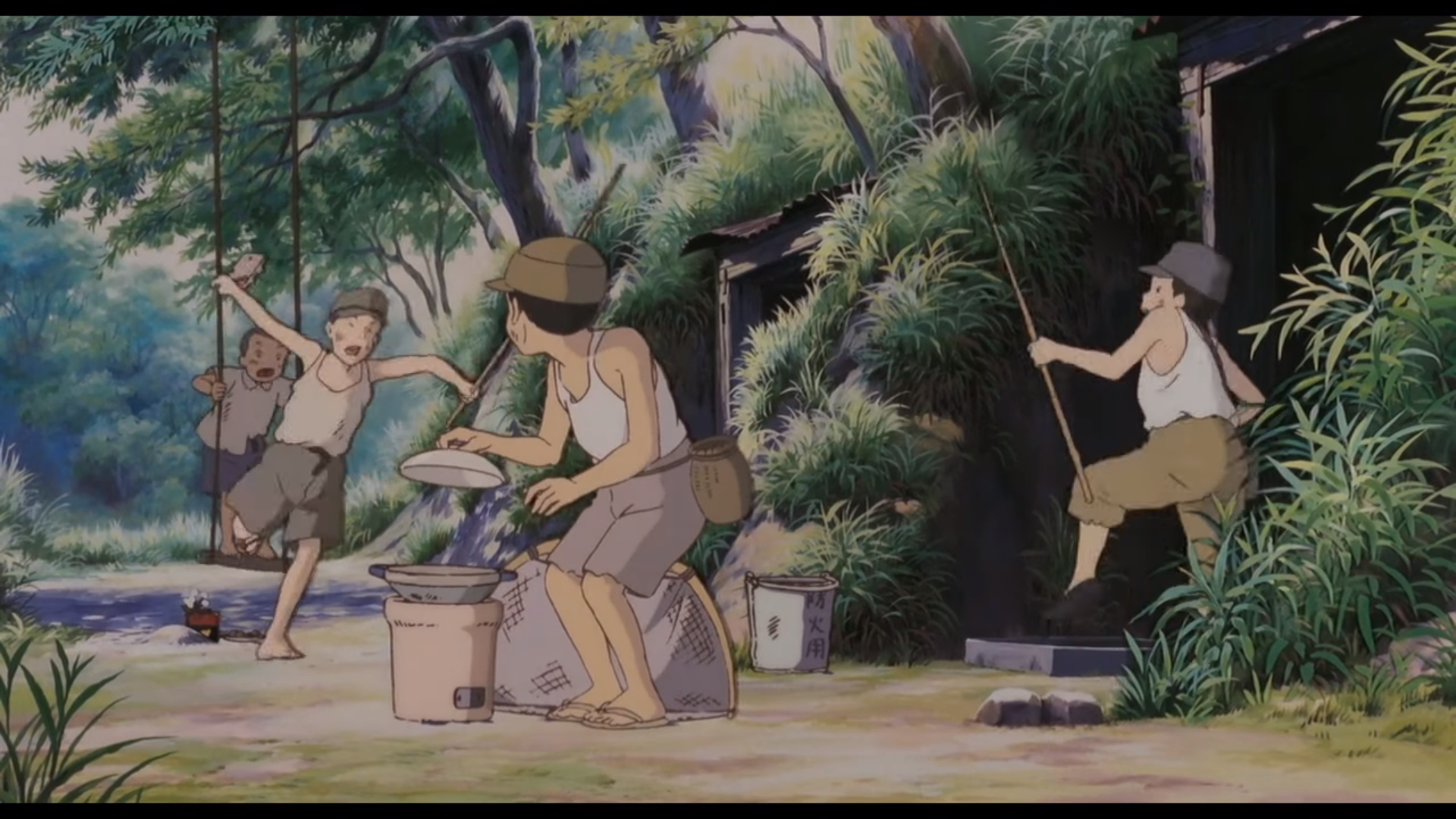

Grave of the fireflies is an emotional experience so powerful that it forces a rethinking of animation. The essential component that makes the film so interesting is the raw density of ideas that it wants to get across in such a short runtime. The movie is centered on the drama of its two main characters that give the viewer the modest impression that it’s exclusively about these kids and the struggles that they face in the World War II era of Japan. Having grown up in the same era, Takahata instills a horror that wars realize in a society that is burdened with famine, loss and disease. That it might press upon the viewers to ponder over the actions of each character. And I might point out that the film, although seems to be invested in exploring the two characters, doesn’t have a monolithic idea that it centers on. Rather, it really explores a variety of thematic and emotional tensions and pushes the audience to grapple with a bunch of conflicting and unsettling ideas. The most obvious idea that the film plays with is that beauty and childlike innocence are fragile and short-lived. This idea is broadcasted by the title of the movie “Grave of the fireflies” which refers to this scene from the movie where Seita and Setsuko get a bunch of fireflies for their cave.

However beautiful, the fireflies are dead by the morning indicating the fact that audience has to come to terms with. Beauty is fragile and delicate. In the beginning of the movie, the film makes an emphasis on how Seita makes a big deal out of not losing his mom’s ring, giving the audience the impression that this ring is going to mean something. But after the only scene, the ring is never spoken of again. This symbolizes the changing importance of things that always makes us prioritize our needs. Instead of this ring, the symbol of permanence and stability is associated with the fruit drops that Seita gives to Setsuko. Like the fireflies, these candies are able to provide one brief, joyful experience to a kid who doesn’t have much left and like the fireflies, they are ephemeral. And these ideas are connected to the characters themselves with Seita and Setsuko’s temporary and blissful childhood.

Why does all this happen? Why is the world like this? And here is another idea that presents itself into the film. Concentrating on the death of Setsuko, we’re left wondering who is responsible for it. The answer, simply enough, is everybody. The choices that people make ripple down into the dying state of the society. The Americans decide to go to war after the Japanese decide to bomb Pearl Harbor. When their mother dies, the kids move in with their aunt who treats them like second class citizens. Because of this, Seita decides they should live off on their own, and then the kids starve. The farmer decides that he can’t afford to sell them anymore food. After Seita decides to steal, the farmer beats him up brutally. The cop shows him some compassion but offers him just a glass of water. The doctor just suggests that Setsuko needs some food and decides nothing to do about it. The point of the movie is not to vandalize these characters but instead the audience is presented with contradictory facts that they have to settle with. First, the society is struggling and the people are doing as much as they can to help each other. Second, the decision that every person takes results in death of a child. Everybody can be blamed but most people did nothing wrong. The film continues providing the audiences with many thematic tensions throughout the films where we observe that things the audience primarily desire end up being awful choices. For instance,

Looking at the awful way that the aunt treats the protagonists, it’s natural to want one of the two things to happen, either the kids can change their situation and make it livable or the kids can escape the situation and find a better place for themselves. But neither of those gestures can really amount to anything. The kids can’t change the situation in World War II era Japan and how could they? Their attempt to leave their aunt’s house only results in starvation and despair which is indicated by the farmer in the middle of the movie where he asks Seito to go back to her. From Seito and Setsuko’s perspective, the system is totally broken. There is not enough food to go around and the woman who’s supposed to take care of them is cruel and selfish. But the possibility of surviving after leaving that broken system was none. This is where the film presents the audience with another conflicting idea. The things that the protagonists face are heart wrenching and tragic. But the sheer possibility of the same sequence occurring with anyone else is forgotten. When you present the film like this by isolating its theme and putting the story in right order, it starts to get a bit overwhelming. It seems that the movie just wants to get at a bunch of interesting feelings but doesn’t really care about having an intellectual through-line. But there is a connective tissue that links the various ideas in the movie together. It’s normal in most movies to be able to blame the main conflict on one entity, either the antagonist or the protagonist. But Grave of the Fireflies says that everybody is to blame. And as opposed to Miyazaki’s theme of revolution, where the character who’s in a bad system changes the system, Isao Takahata emphasizes on idea that sometimes we need to stay in the broken systems. Sometimes, we have two choices- remain in a bad place or die trying to escape it. It’s normal to expect a story to frame its main characters as the only things of importance to imply that we are focusing on them for good reason but Grave of the fireflies explains that there are countless tragedies that we could have talked about.

And there’s something deeply incidental about the facts talking about this one. The very first line of the movie has Seita telling us the date he died. And since he’s alone when he dies, we can extrapolate that Setsuko’s dead too.

From then on we just follow Seita’s ghost as he watches his and his sister’s final days unfold. It’s hard to overstate the importance of this framing device to the movie as a whole. It informs every second of my experience with it and it makes me feel detached from what’s going on with our characters. There are many scenes in the movie which could have had very different emotional impacts. The sad moment where Seita tries to find food for his sister could feel very different from the comfortable one where they eat rice. The oppressive moment where their aunt is mistreating them could feel very different from the liberating one, where they pack up and leave. But the framing makes sure they don’t feel radically different. When we see them eating food, we recall the moment where Seita gives his aunt his mother’s silk and see Seita’s ghost recoil at how awful that decision was. When I see them go to the woods, there’s no part of me that can relate to a feeling of childhood wonder and adventure because it’s so obviously a mistake. The constant sense of despair that the movie invokes is the opposite of intimacy. Seita and Setsuko experience a million emotions in this movie. Joy, excitement, fear, oppression. But I don’t feel those things. I feed bad and impudent the entire time. And because I can never locate myself in the headspace of the characters, I am pushed away from them. There is one scene that brings out this separation than any other. The kids that discover Seito and Setsuko’s shelter out in the woods.

This scene serves no purpose as far as the plot is concerned but enforces our position as an audience. We are these kids. Like them, we’re just a bunch of people who stumbled upon a tragedy. We have the ability to look at what’s happening and say that our lives aren’t so bad after all. We can go there, feel bad for a second and then, most importantly, leave. The film challenges the act of watching as it does in many other places and problematizes our ability to enter the text and understand what it means in any constructive way. After all, we’re not Seita or Setsuko. Their lives and deaths are not for us to inhabit. All we can be is observers on margin, looking on, from very far away.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: